In August 1910, socialist women from different parts of the North Atlantic region met for the second International Conference of Socialist Women in Copenhagen. This was the first international socialist congress in Scandinavia with delegates even from Sweden. During the first international conference of socialist women in 1907 in Stuttgart, Swedish and Danish women were not able to participate. (1)

Although the 1910 conference might have been the first opportunity for working-class women from Sweden to participate in international proceedings, transnational and international contacts also existed between women in Sweden and abroad in a variety of ways before 1910, although almost no research exists on this topic.

Although the 1910 conference might have been the first opportunity for working-class women from Sweden to participate in international proceedings, transnational and international contacts also existed between women in Sweden and abroad in a variety of ways before 1910, although almost no research exists on this topic.

- Download pdf version of this essay:

Worlds of Women in ARAB’s Collections – A Short Introduction (86 kB)

Towards a Transnational Feminist Labour History

Labour history is one of the fields that can naturally be viewed from a transnational and global perspective. Since the second half of the nineteenth century, the labour movement has been a movement with an international ambition and an internationalist ideology. The movement itself can be regarded as a global phenomenon, not in the sense that it was occurring in all the different regions of the world, but in the sense that it occurred as a phenomenon in many regions of the world, sometimes independent of developments in other parts of the world and sometimes influenced by transfers from similar movements in other parts of the world. An approach to a global labour history has been developed by our colleagues at the International Institute of Social History (IISG) in Amsterdam and has recently been discussed more comprehensively by Marcel van der Linden in his recent book Workers of the World. (2)

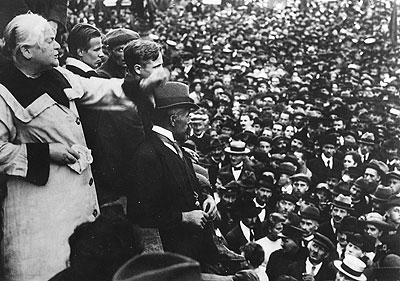

LSI women’s meeting in Brussels. Photo: Nina Andersen Keystone. Source: ARAB, Morgonbris.

While transnational and global labour history has been a refreshing trend in the field of labour history, the role of women in these histories has been neglected. (3) Recent research on feminist women’s international work has shown that the international arena and the transnational connections have played a role in the local, regional, and national political work of women. (4) This is at least true for women in the Western world and mainly for the first part of the twentieth century. When women still lacked political, economic, and social rights, they had no access to both the political arena and the public sphere. Susan Zimmermann has put forward the hypothesis that the international arena could be used to compensate for part of this lack of access. One of the questions is how this was possible and how the situation changed when women gained access to political decision making at the national level. (5)

While research on autonomous/liberal/middle-class women’s organizations has, first and foremost, concentrated on the international arena, we know very little about the international organizing of working-class women. Very little is known about the conditions for different groups of socialist and/or trade union activists. Moreover, we have scant knowledge of their transnational connections and how the different levels of activism interacted. A global approach to feminist labour history adds new contents and insights. Our intention with this overview of available sources at the Labour Movement Archives and Library (ARAB) does not intend to and cannot provide instructions for a global historiography of feminist labour history, but our aim is to inspire researchers, both academics and those actively interested in researching their own history, to look beyond national borders. Instead of fully covering the material stored at ARAB, we have chosen a number of themes that deal with women’s transnational connections. In addition, we have created a database with an overview of relevant archival material.

Scattered Sources on Women’s International, Transnational, and Global History

Delving into archives is sometimes like going to a jumble sale. Apart from piles of old dusty books and papers, sometimes the visitor can discover both small and large treasures. The material that might be useful for an analysis of transnational connections is only a small part of the archival material at ARAB. With a few exceptions, the collections do not contain any major archives of international women’s organizations, but, nevertheless, these international organizations have still left their mark in the Swedish material. Most of the material is in Swedish, but, for the first half of the twentieth century, the largest part of the non-Swedish material is in German; after the Second World War, English is dominant, but there is also material in French, Spanish, and Russian. The material is scattered and can be found in a lot of different archives: those created by men and women, and those by Swedish and non-Swedish organizations.

Clara Zetkin (1857-1933). Source: ARAB, Postcard collection.

Presenting available sources means, therefore, always a selection and categorization of material. Also the concepts of international and transnational have changed over time. Both concepts have been used in order to collect materials that either concern ideas and historical processes outside Sweden, both referring to international bodies and/or other countries, or different aspects, stages, and parts of transnational exchange processes that took place between Sweden and other regions of the world. The connections existed between individuals, between individuals and organizations, between different national organizations, or between supranational and national organizations.

This makes it rather difficult to determine the scale of the material on women’s international and transnational connections. While materials stored in the archives are scattered, the printed materials, such as bulletins and journals published by international organizations, or journals published by other non-Swedish organizations, often include a longer series and generally cover a longer period of time. These printed matters are sometimes even more complete than those in the holdings of other archives and libraries outside Sweden. In other words, the printed material is much more comprehensive than the archival material. The fact that a specific printed matter is available in Stockholm is in itself a result of the transfer processes initialized at the turn of the nineteenth century. Socialist women’s journals have been exchanged between different national organizations and, despite the fact that probably only few women could read Swedish outside Sweden, the Swedish journals were exchanged and Swedish socialist women received the journals from women’s organizations in a whole range of different languages.

Searching the Collections

British delegation at the LSI women’s congress in Paris in 1933. Photo: (No information.). Source: ARAB, Morgonbris.

While it is easier to get an idea of the international material, and the international material on women, by using the library’s online search engine Kata, it is still relatively difficult to search the archival holdings. The archival lists might say that the archive contains printed matter, but they do not always list them in detail. In order to make the archival material at least a bit more accessible, we have drawn up a list including all the archives that have been categorized as ‘female’ in the National Archival Database of Sweden (NAD). This categorization is a difficult one for several reasons: first, the categorization does not refer to the material contained in the archives, but to the gender of the person who created the archive, which excludes men who were politically active in promoting gender equality. Hjalmar Branting’s personal files include, for example, more letters from Clara Zetkin than the Social Democratic women’s organization. It also means that it can include archives from women who were not at all concerned with feminist politics. Second, it includes organizations that were classified as women’s organizations. As a consequence, other organizations, such as the Communist Party or the Social Democratic Party, are not included despite the fact that they were concerned with women’s issues and might even have had a women’s committee. The second limitation is the probability of finding archives that include transnational or international material. Should the personal files of refugees be classified as international or transnational? Although the person has lived in transition and is likely to have transnational connections, it cannot be said for sure that the materials stored at ARAB include any of this type of material. We have been dealing with these technical problems in what could be called a rather generous way by including all the archives that contain international material, even if it is sometimes only a passport.

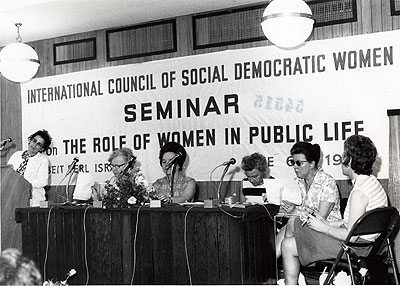

International Council of Social Democratic Women in 1971. Photo: (No information.). Source: ARAB, Morgonbris.

In order to compensate for the difficulties in finding all of the relevant archival material, we have chosen to pick some themes that are of special interest to transnational feminist labour history. Despite the fact that the international arena only included a small number of the members of the labour movement, this does not mean that the decisions and exchanges that took place there did not inspire those ‘at home’, i.e. those who ‘could not come’. In what ways the international arena and developments in different parts of the world inspired new projects in other places needs to be investigated. Many of these exchange processes did take place by reading and writing, especially during the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century.

In his article, Martin Grass writes about Clara Zetkin’s letters sent both to the Social Democratic women’s organization and to leading Social Democrats in Sweden. There are only a handful of letters, but those to the representatives of the women’s organization tell a lot about the character of and conditions for women’s international work. Networking with men from the movement was often essential for women in order to develop their own organizations and groups and Zetkin’s letters to male leaders of the labour movement illustrate this. Zetkin wrote standard letters to women in Social Democratic organizations in different countries in the years before photocopying was a standard method for duplicating information cheaply. She asked about the number of members, the ways they conducted their political work, and reported about her own work both in Germany and as the secretary of the International Women’s Bureau. Today the instructions and the questions would probably be published on a website. Using this method, Zetkin was able to collect information and statistics on socialist women’s organizing in different parts of the world, although mainly in Western countries.

What international Swedish journals were like is shown in the piece by Eva-Karin Annemark and Mats Myrstener who have written an overview of the articles published in the journal Morgonbris during some of the years at the beginning of the twentieth century and some of the years during the 1970s that report on different international issues. Morgonbris is yet another example of this and what is illustrated by the long list of articles reporting on the world outside Sweden applies as well to not only other Swedish journals, but also foreign journals that belong to the labour movement press. The very first articles in Morgonbris also included articles by Zetkin translated into Swedish, a practice that was probably used in many other journals and that allows us to understand that ideas were spread in time and space and how this was done. Many of the articles were translations of articles written by leading labour women abroad.

Morgonbris was, however, not only a medium for conveying information from abroad to Swedish readers. Censured articles from Gleichheit were published in Swedish in Morgonbris as well as the conversations between British and German socialist women during the First World War when meetings between the two national organizations were not allowed-the British women were not given passports to travel to the peace conference in The Hague. The message from British Labour women to their German sisters was originally published in the British journal Labour Woman; it was then translated into Swedish and so was the German women’s letter to the British Labour women’s executive committee. Why, then, were all these texts translated and what was the idea behind it? One of the reasons for the publication of the British and German communication is probably the fact that British and German socialist women were the strongest socialist women’s groups in the International, often on different sides of the political questions. Publishing the contacts between the two of them gave a glimpse of the attempts by both organizations to secure peace, despite the fact that their male comrades on the two opposite sides of the battlefields were fighting each other during the First World War.

But the publication of international reports in Swedish journals was an important way for recently established organizations to not only show the successful development in other foreign movements and to inspire political action, but also to create a feeling of internationalism. In addition, postage for journals was subsidized in Sweden, which made it a comparably cheap way of conducting agitation.

Lâle Svensson tackles the subject of political tourism in transnational connections. She describes travelogues in the form of not only letters, but also in more formal reports published in journals. Political tourism in a very broad sense has been important for the Swedish labour movement from the very beginning. For example, August Palm worked in Germany and later even travelled to the United States as an official agitator paid by the American labour movement. Svensson shows how political tourism among Swedish women changed from journeys to the modern Soviet Union during the 1920s, to the war-stricken countries to help their sisters in need, and twenty years later to the Global South in order to support women’s projects in Africa and Asia.

After the Second World War, Sweden became also one of the major destinations for political tourism from other parts of Europe, the United States of America, and Australia. Much of this still needs to be investigated and would certainly contribute to our understanding of the notion of the Swedish model and its feminist implications.

Arne Högström presents the transnational connections through the personal files of Brita Åkerman, who was active in different women’s organizations and was among the directors of Active Housekeeping, an information bureau within the State Information Board, and later even of the Swedish Consumers Agency. Högström’s presentation illustrates the exchanges that took place when Åkerman was abroad attending conferences and exhibitions on active housekeeping, forming an active women’s consumer politics in interaction with international development. Åkerman’s political work is yet another example of what was seen as typically Swedish, which, at the same time, was influenced by the developments outside Sweden. Consumer politics has always been about transnational and global connections, in which women became involved early on. This is an issue that would certainly need more empirical research.

International Women’s Day is one of the socialist inventions that have spread and become a successful feminist celebration all over the world. In my own piece, I try to shed light on the development and the implications of International Women’s Day from the decision at the Copenhagen conference in 1910 to the present day. The significance of International Women’s Day has certainly changed since its inception when it was intended to function as an international day for agitating for women’s suffrage to when it became an official United Nations Day in the 1970s to the present day when it is used by major companies to celebrate their outstanding female employee. International Women’s Day also functions as a prism for women’s international work and their international ambitions over time and in this way provides a starting point for a study of this historical development.

Lars Gogman writes (Coming soon!) about the international contacts of communist women, and shows how deeply rooted Swedish communist women were in an international movement. Little has been written on communist women in Sweden until now, but even less on their international connections.

This overview is unfortunately lacking a survey of the sources on feminist labour activists from trade unions. Moreover, a more thorough overview of women’s solidarity work in the Global South is also only touched upon and would need more attention. This is however a project that has started and we hope to be able to publish further essays in the future.

Despite the fact that, as previously mentioned, we can only present this limited selection of materials relating to working-class women’s transnational connections, we want to inspire the reader of this overview to conduct further research: war, love, peace, and understanding-it’s all in there!

References

1

For an analysis of debates on nightwork prohibition on international conferences see Ulla Wikander, Feminism, Familj och medborgarskap. Debatter på internationella kongresser om nattarbetsförbud för kvinnor 1889-1919, Göteborg 2006.

2

Marcel van der Linden, ‘Globalizing Labour Historiography: The IISH Approach’, (2002) <http://www.iisg.nl/publications/globlab.pdf>, accessed [16 August 2010]; Marcel van der Linden, Workers of the world: essays toward a global labor history, Studies in global social history, 1, Leiden 2008.

3

Pernilla Jonsson, Silke Neunsinger, and Joan Sangster (eds.), Crossing Boundaries: Women’s Organizing in Europe and the Americas, 1880s-1940, Uppsala, 2007.

4

- Ulla Wikander, Feminism, familj och medborgarskap: debatter på internationella kongresser om nattarbetsförbud för kvinnor 1889-1919, Göteborg 2006.

- Susan Zimmermann, ‘Frauenbewegung, Transfer und Trans-Nationalität. Feministisches Denken und Streben im globalen und zentralosteuropäischen Kontext des 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhunderts’, in H. Kaelble, M. Kirsch, and A. Schmidt-Gernig (eds.), Transnationale Öffentlichkeiten und Identitäten im 20. Jahrhundert, Frankfurt/Main/New York 2002., 263-302;

- Bonnie S. Anderson. Joyous Greetings: The First International Women’s Movement, 1830-1860, Oxford; New York 2000.;

- Karen Offen, European Feminisms: 1700-1950: A Political History, Stanford, Calif. 2000;

- Margaret H. McFadden, Golden Cables of Sympathy: The Transatlantic Sources of Nineteenth-Century Feminism, Lexington 1999;

- Laila J. Rupp, Worlds of Women: the Making of an International Women’s Movement, Princeton, N.J. 1997;

- Ulla Wikander et al., Protecting Women: Labor Legislation in Europe, the United States, and Australia, 1890-1920, Urbana, Ill 1995;

See also ongoing research by, e.g, Eva Matthes, University of Augsburg, on the discourses within ICW and national Council of Women of Germany; and Susanne Schötz, TU Dresden, on ‘Allgemeiner Deutscher Frauenverein’ and international communication. Most of the research concerns bourgeois women’s organizations as Zimmermann, ‘Frauenbewegung, Transfer und Trans-Nationalität’, 263-302, 265 fotnote 6 has pointed out.

For exchange between socialist women see

- Karen Hunt, Equivocal Feminists: The Social Democratic Federation and the Woman Question: 1884-1911, New York 1996, p. 63-70;

- Christine Collette, The International Faith: Labour’s Attitude to European Socialism, 1918-39, Studies in Labour History, Aldershot 1998.

For research on international women’s congresses, including socialist women, see also

- Ulla Wikander, ‘Suffrage and the Labour Market: European Women at International Congresses in London and Berlin, 1899 and 1904′, in Jonsson et. al. (2007);

- Silke Neunsinger, ‘Creating the International Spirit of Socialist Women: Women in the Labour and Socialist International, 1923-1939′, in Jonsson et. al. (2007);

- Antje Schrupp, Nicht Marxistin und auch nicht Anarchistin: Frauen in der Ersten Internationale, Königstein, 1999.

See also Dorothy Sue Cobble, „Vänskap bortom Atlanten. Arbetarfeministernas internationella nätverk efter andra världskriget” in Arbetarhistoria 2009: 129-130, 12-20.

5

Zimmermann (2002), 263-302.